Ms. Member of the European Parliament, dear Emma RAFOWICZ,

Ms. Director General of the Norwegian Film Institute, dear Kjersti MO,

Dear Marine FRANCEN and dear Frédéric SOJCHER,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Friends,

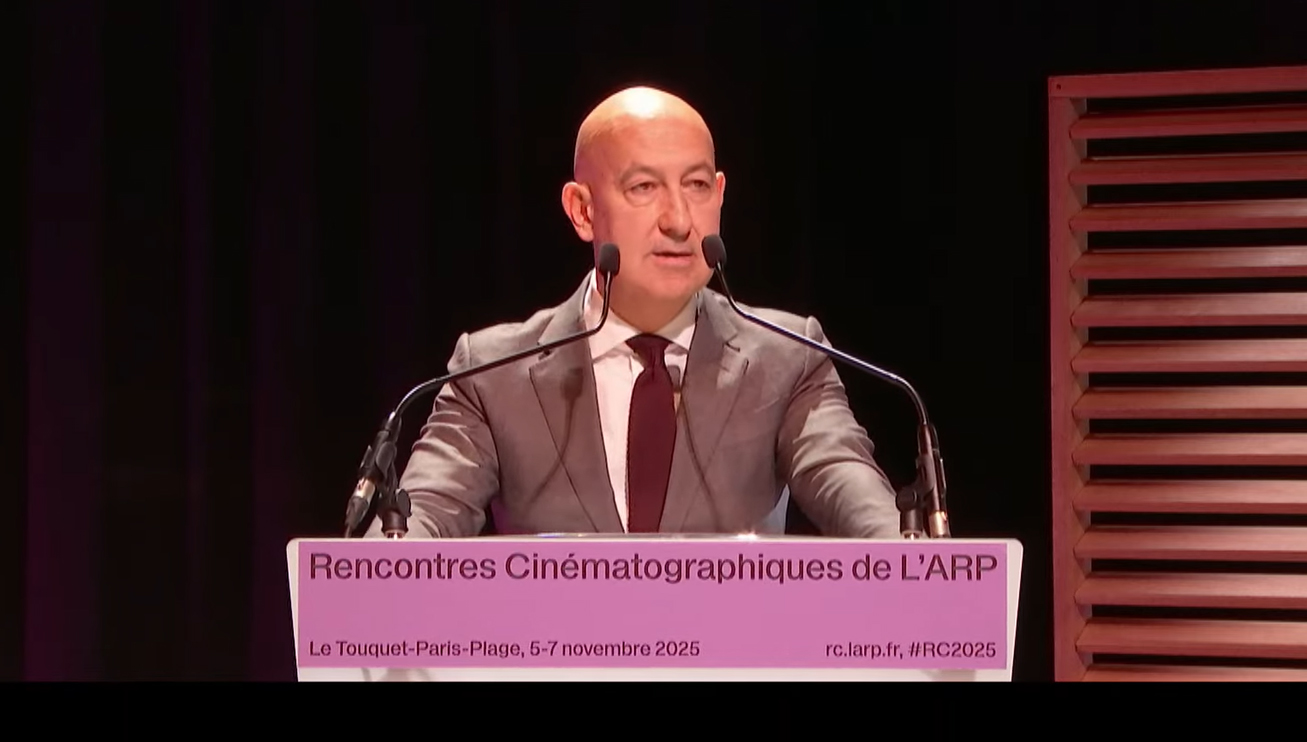

I am very pleased to open these 35th ARP Meetings, because they remain a place for rigorous debate on the future of cinema.

Rigorous, because the debate is not confined to France: the composition of this first transatlantic roundtable extends from Scandinavia to Italy, passing through France and the United States.

Rigorous also because you have brought together all perspectives: that of professionals – in this case, two screenwriters: an American, dear Howard RODMAN, and an Italian, dear Francesco RANIERI MARTINOTTI – that of academic research, dear Chloé DELAPORTE, and that of public authorities, whom I have already mentioned.

The topic that brings us together this morning, “Transatlantic Dialogue: What Weapons for Culture?”, is one of eternal relevance: nearly 80 years ago, the CNC was created as a counterpart to the Blum-Byrnes Agreements, which governed the conditions for film exchanges between both shores of the Atlantic.

However, the terms of this dialogue have evolved considerably in recent years – not to say in recent months.

Indeed, the transatlantic dialogue once concerned, on the one hand, French and European cinema, and on the other, the Hollywood studios. In short, family affairs among people of the cinema. And as Michel Audiard wrote, “family matters are like faith – they command respect.” Those were almost the good old days, even if some members of the family occasionally made you offers you couldn’t refuse.

Today, the transatlantic dialogue has changed in nature.

For works are now distributed – or reused – by American companies, almost all of them, many of which are, by their very nature, external to the cultural sphere. They are the platform companies, the social networks, and now, those in the field of artificial intelligence. Their turnover, or market capitalization, exceeds the wealth of most nations: they have, to extend the metaphor, “the firepower of a cruiser and match-grade guns.” And for most of them, cinema is but one issue among many.

What lies at the heart of the “Transatlantic Dialogue – 2025 Revised,” I believe, is precisely the participation of these new American actors in the global economy in the financing of creation – participation both upstream, at the stage of investment in production, and downstream, in the sharing of revenues from distribution.

And I do mean creation in general, not merely French or European creation. For after all, dear Howard RODMAN – and we will also hear a message from Russ HOLLANDER on behalf of directors – this issue is as much yours as it is that of your French and European colleagues. You have moreover set an example of successful mobilization through the 2023 screenwriters’ strike, which enabled you to obtain from studios and platforms better salaries, a fairer share of revenues generated by streaming, and guarantees on employment and the protection of your works with regard to AI.

But it is precisely in this context, marked by a balance of power objectively more unequal than ever before – and where regulation is therefore more necessary than ever – that the foundations of the French and European ecosystem are being attacked: public aid and the investment obligations imposed on broadcasters to renew creation; the obligations of these same companies to broadcast European works; and the tax credits designed to prevent the relocation of our industries exposed to fiscal dumping.

They are under attack across the Atlantic – and I will return to that shortly.

But they also risk being weakened from within our own country. A word on that point.

What does the film and moving-image sector represent in France?

It represents 260,000 jobs and a share of national wealth equivalent to that of the hotel industry, two-thirds that of the automobile sector, and greater than that of metallurgy. It is an industry whose very principle is innovation; one that exports not only its productions but also its expertise and talent, whose excellence is recognized worldwide.

The performance of this sector can also be measured in our cinemas: in 2024, 45% of the box office in France was accounted for by French films – compared with 26% in Italy and 9% in the United Kingdom.

It can also be measured across our regions, since 90% of the French population has a cinema within 30 minutes of home, which explains why two-thirds of them go to the movies each year – and more than 80% in the case of young people aged 15 to 25.

This performance is also visible in the public accounts, since all the CNC’s support policies for the sector – from professional training to film distribution, including writing, production, and distribution – are entirely financed by a special levy paid by the companies in the sector, without costing the State’s taxpayers a single euro. As for our tax credits – probably the best-assessed in all French taxation – they enable more than 90% of the production expenditure of our companies to remain on national soil – what other industry can claim as much? – for a net fiscal cost of less than €50 million, itself more than offset by the economic benefits generated by that localization.

We could continue this litany of indicators much longer.

I would rather conclude it with a more intangible but essential consideration. At a time when we are reflecting on ways to regenerate democratic life, let us not lose sight of the fact that there can be no public debate, no “polis” in the political sense of the term, unless citizens share a common foundation of references: linguistic, moral, historical, even mythical, but also cultural. This “common world,” without which democratic debate is impossible, is powerfully shaped, transmitted, and enriched by cinema – that infinitely popular art.

So, under these conditions, how can one contemplate weakening a system that costs nothing to public finances – since it generates as much revenue as it uses – and that achieves all the cultural and industrial objectives of general interest assigned to it?

I do not believe one can, at the same time, jump up and down like a jack-in-the-box shouting “national sovereignty! cultural sovereignty! reindustrialization!” and then contemplate – precisely at the moment when our industry, our culture, and our sovereignty are being challenged across the Atlantic – a unilateral disarmament consisting, for example, in diverting the CNC’s resources, even abolishing it altogether, or dismantling our fiscal defenses against relocation.

What strange self-hatred, what death wish, could drive us to shoot ourselves in the foot in this way, when we are leading the European – even global – pack in so many respects?

For it is precisely because our model works – because it costs the State’s taxpayers nothing, because its films fill our screens, because it produces and creates value in our country, because it allows us to retain control over our own stories, because it makes France shine throughout the world – that it is being challenged, unilaterally and unjustly.

Rather than undermining its foundations ourselves, rather than weakening it from within, let us instead mobilize and close ranks, to dismantle caricatures and disinformation, and thus restore dignity and fairness to the transatlantic dialogue.

And in this respect, there is much to be done!

Our only consolation is that we now find ourselves in the same boat as our European partners.

Our regulatory framework is being attacked both by the American public authorities, in a rather novel and thunderous style – VERY STRONGLY – and through the more familiar forms of lobbying and litigation. At the core, these attacks are fueled alternately by the cynical arguments of an unrestrained will to power, or by a more abstract discourse invoking freedom of enterprise, free trade, and innovation – said to be constrained in Europe by a regulation both discriminatory and ineffective.

Nothing truly new, then, except in form. But in a context of unprecedented imbalance between the two sides of the Atlantic – at a time when the richest companies in the world are no longer those of oil or automobiles, but those of new technologies – we must be less naïve than ever.

For in truth, the debate does not oppose the camp of public intervention to that of freedom. Nowhere have public authorities refrained from intervening in cinema and the audiovisual sector – least of all in the United States. The recent example of the forced divestiture of TikTok’s American operations, or other, more or less orchestrated capital movements, illustrate this vividly. To intervene, or not to intervene – that is not the question. The real question is: since intervention exists, which model of regulation do we choose, and in pursuit of what objectives?

In this respect, the recent American protectionist announcements will at least have the merit of dispelling any illusions in France and in Europe – one may hope.

Granted, the notion of “customs duties” on films shot outside U.S. territory will primarily harm the American industry itself! It is a slapstick comedy in which we Europeans would be, for the most part, spectators.

Nevertheless, the entire list of our regulatory mechanisms lies on the table of the U.S. Trade Representative, each identified as a “barrier to trade” – from the tax on cinema tickets to the investment obligations, including programming commitments.

We must also keep in mind the direct attacks by American companies against the regulatory frameworks of our neighbors.

I am thinking of French-speaking Belgium, where investment obligations are being challenged by streamers before the Constitutional Court – and perhaps, ultimately, before the Court of Justice of the European Union. The same applies to the Flemish Community, which finds itself opposed to video-sharing platforms. These legal battles could weigh heavily on the future room for maneuver of all EU countries. And we cannot conclude this tour of Europe’s litigation without mentioning the challenge brought against the ministerial decree extending our media chronology rules.

Yet, if anything characterizes the European and French model, it is openness to the world, neutrality, and the absence of discrimination based on the origin of companies or artists.

For the numbers speak for themselves: American films account for 69% of box office admissions in Europe, while European films are almost invisible in the United States.

It is neither out of masochism nor coercion that great filmmakers such as Richard LINKLATER or Jim JARMUSCH have chosen to shoot their latest works wholly or partly in France; that Brad PITT has joined forces with Mediawan to create his production company; or that Natalie PORTMAN co-produced Arco, the animated film by Ugo Bienvenu.

If French regulation truly obstructed exchanges, would 27 countries out of 86 have chosen, this year, a co-production with France to represent them in the race for the Oscar for Best International Feature Film?

In short, to label as punitive and discriminatory a model that, on the contrary, seeks to rebalance power relations, prevent monopolies, and guarantee cultural diversity – a model that welcomes American talents, works, and enterprises with open arms – is an Orwellian rhetoric, the very same in which the Ministry of Truth dispenses lies and the Ministry of Peace wages perpetual war.

This inversion of meaning has been rightly identified by the European Parliament in its recent and most significant Resolution of 23 October 2025, defending the investment and broadcasting obligations for European works set out by the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD).

This brings me, finally, to the two items on the EU agenda that will largely determine our capacity to preserve cultural diversity and sovereignty in Europe and in France.

The first of these concerns the Budget.

The European Commission has recently presented its proposal for the 2028–2034 framework, which increases the potential resources devoted to European cinema and audiovisual production. However, this project raises many questions that France will be addressing in the coming months – and we hope we will not be alone. Indeed, the proposal, entitled AgoraEU, embodies a new approach, as it is meant to support not only culture and media, but also “active citizenship, rights, and values.”

This rapprochement can be viewed positively: in doing so, the Commission acknowledges that creative works are not merely a cultural and industrial issue, but also a key to the future of our democracies.

But, in that case, we must take the Commission at its word: we can no longer be satisfied with half-measures, neither in terms of resources nor of principles.

On the matter of resources, the increase in the AgoraEU envelope must serve cultural priorities, and we will be committed to ensuring that it does. Among our key interlocutors, I trust we can count on the European Parliament, which has been – as before – the foremost ally in strengthening the current Creative Europe programme during previous budget negotiations.

As for principles, the Commission’s proposal, at this stage, does not target independent production, nor support for theatrical distribution. Here again, we will be mobilized to reintegrate these essential “hallmarks” of diversity.

But to achieve this, we need your help. To secure European funding for these priorities, we must be able to demonstrate to the Commission how such funding concretely strengthens the bond between works and audiences.

The second major topic on the European agenda is the cornerstone of our sector: the Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD).

As you know, this directive could be reopened at the end of 2026. In Brussels and in the capitals, its evaluation has already begun.

France has drawn a very positive assessment from its transposition – as evidenced recently by the strong theatrical results of Ma mère, Dieu et Sylvie Vartan and Un ours dans le Jura, both financed by Amazon and Netflix under their investment obligations. I am also thinking of the release in cinemas of the first animated films financed by streaming platforms, such as Marcel et Monsieur Pagnol or Arco.

Naturally, we will emphasize these results to the Commission to encourage it to preserve the existing mechanisms, while also reminding it of the importance of leaving Member States sufficient flexibility in their transposition to adapt to changing circumstances.

For instance, when we realized that our transposition was not yielding results for minority genres in the audiovisual field – animation and documentary – the Minister of Culture took the initiative to revise our framework. The Commission did not object, and the Conseil d’État, following Arcom, will soon examine the draft decree. This flexibility illustrates the pragmatism of our approach.

Moreover, the directive currently contains certain limitations that could usefully be discussed if it were indeed reopened. These are the avenues outlined in the Raynaud Report that I presented last year.

First, to tighten the definition of a European work, in order to prevent entirely extra-European productions from sailing under this flag, thus emptying investment and broadcasting obligations of their meaning.

Second, to improve the visibility of our works by allowing each Member State to set, in its national legislation, more ambitious broadcasting quotas for all actors targeting its territory.

And finally, to create fairness between linear and non-linear broadcasters, by raising the quota for European works from the current 30% to a minimum of 50%.

We have shared these proposals with our European counterparts within the EFAD framework, and I believe – dear Kjersti – that they have found some resonance beyond our borders.

Those are the two matters already on the European agenda.

And then, of course, there are the recurring issues that we must not lose sight of.

I am thinking of the attacks on geo-blocking, which keep resurfacing, despite its essential role in financing creation.

I am also thinking of artificial intelligence and the sterile opposition, endlessly invoked, between innovation and regulation – whereas legal certainty is, on the contrary, one of the conditions for innovation.

I know that some of you are growing impatient and have been disappointed by the results of the AI Regulation. But I have no doubt that, in the long run, if the political will remains, we will integrate this technological revolution, as we did previous ones, into our model of financing and distributing creative works.

At our level, within the CNC, we have taken the initiative using the levers available to us: by requiring transparency from project leaders; by giving them the option to oppose the use of AI in the assessment of their applications; by holding members of our commissions accountable if they use AI in their work; and by creating an observatory to regularly assess the various impacts of this technology.

The CNC is therefore fully committed to ensuring that French and European regulation evolves in the right direction — in the service of cultural diversity, within the framework of our model open to the world. We work tirelessly with our partners in other Member States. For example, last spring, we succeeded in mobilizing, within a few days, the European Ministers of Culture in the run-up to the Cannes Festival, where they issued a joint declaration in support of our model. The recent American announcements make this European solidarity more vital than ever.

But these announcements also confirm the necessity of national cohesion within France around that national treasure which is our film and audiovisual industry.

Naturally, our mechanisms are not perfect, and improving them is a continuous process. We are the first to say that the CNC must constantly question itself, to adapt to the needs of creation and dissemination of works: thus, we have just placed media literacy at the heart of our strategic priorities. The CNC must also ensure diversity in its choices of support, as well as neutrality – as every public service must, for neutrality is not only a legal obligation for public service, including that entrusted to the CNC, but also one of the conditions of citizens’ trust in it.

If, therefore, our mechanisms remain open to improvement, I believe it would be irresponsible to use any occasional shortcoming as a pretext to disregard the artistic, industrial, societal, and democratic achievements of which the CNC is the guarantor – and which inspire the admiration of all our partners around the world.

Granted, our country is going through a very particular political context.

Granted, the situation of our public finances may explain a certain nervousness, both from the media and from political leaders, whose task today is particularly arduous.

But we must keep in mind that the things which are good – especially when they are collective goods – take a very long time to build, whereas they can, on the other hand, be irreparably compromised in an instant, by a single hasty decision.

Such prudence at the helm is all the more essential in times of strong headwinds over the North Atlantic…

But you can count on the CNC to chart the course.

Thank you for your attention.